Doing fieldwork with my own family on the invisible disease of FMF

Anthropologists often study another culture than their own and understanding those who are different from us can be a challenge. But studying something very close and familiar can pose other types of challenges to anthropologists and still lead to significant revelations. Simge Nur Yildiz from Turkey who is an MA student in anthropology at Tallinn University School of Humanities is reflecting on the experience of doing fieldwork with her own family.

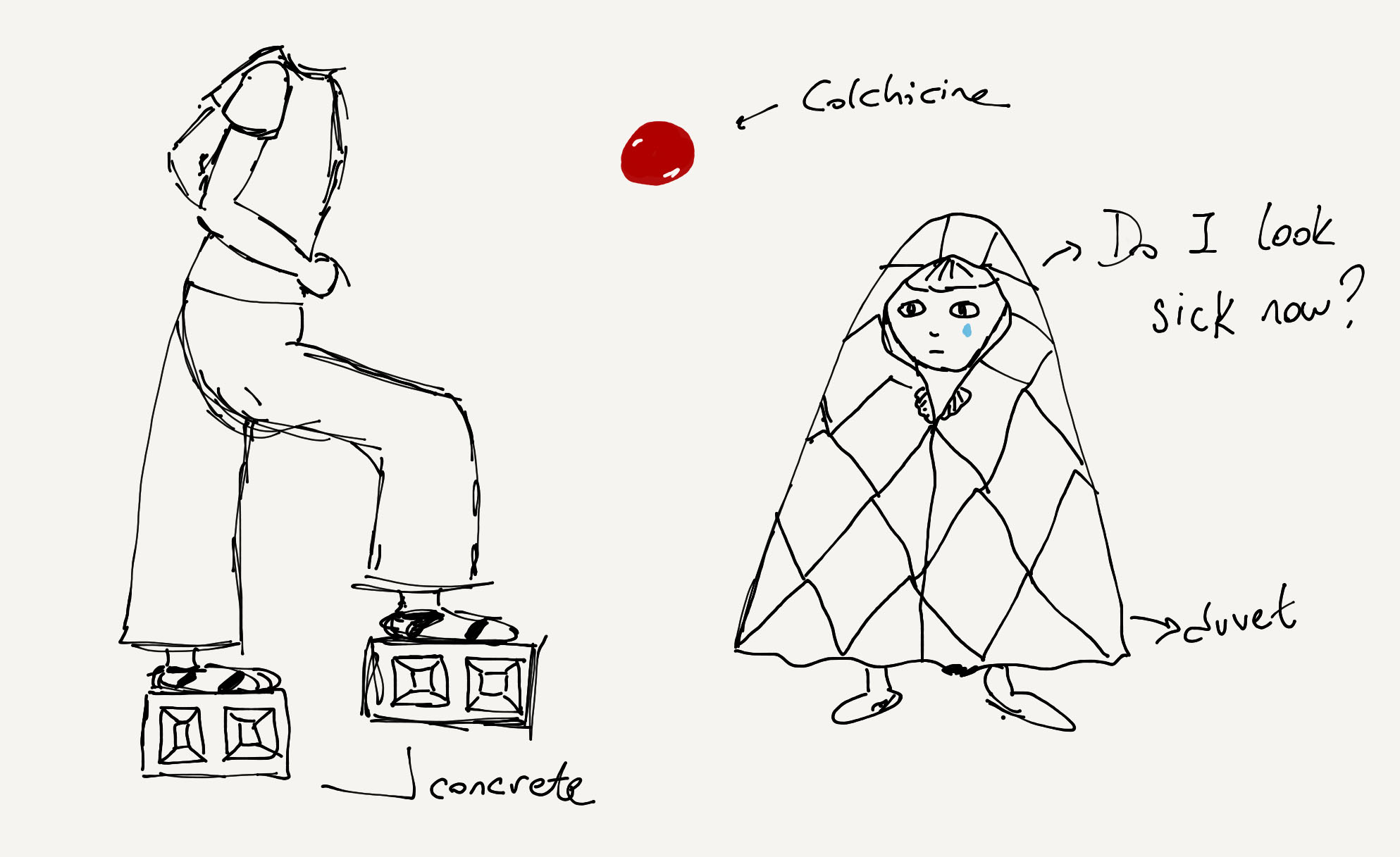

Each and every one of my family of five suffer from a chronic and rare disease called Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF). It is an inherited autoinflammatory disease for which there is no cure and requires lifelong therapy of Colchicine to treat the symptoms and prevent the deadly outcome. FMF patients are often misdiagnosed, mistreated due to lack of knowledge of it and also symptoms resemble various diseases which can lead to delays in diagnosis.

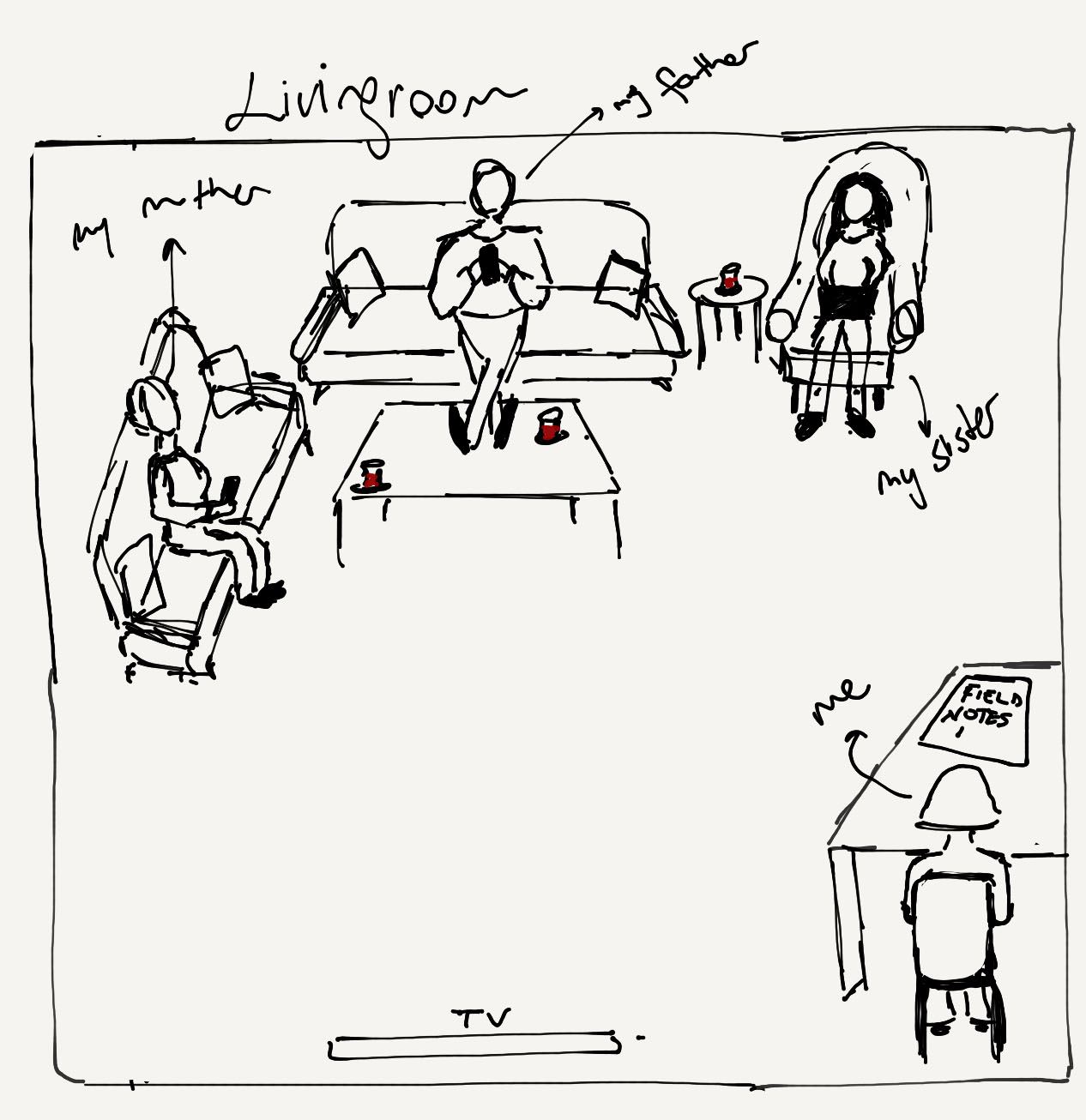

For my MA thesis in anthropology, my aim was to explore what a family with FMF means by invisible illness and how they make use of this perception to explain their lives. I spent two months (July-August 2020) conducting ethnographic fieldwork in our family home in Turkey. It was chaotic during the first week of my fieldwork because of role confusion or conflict. I was simultaneously a researcher, a daughter, and a sister, therefore, I was not sure if I was doing it right. Constantly going back and forth between the data and my understanding of it and the circulatory communication between us helped me to conduct fieldwork in a balanced way.

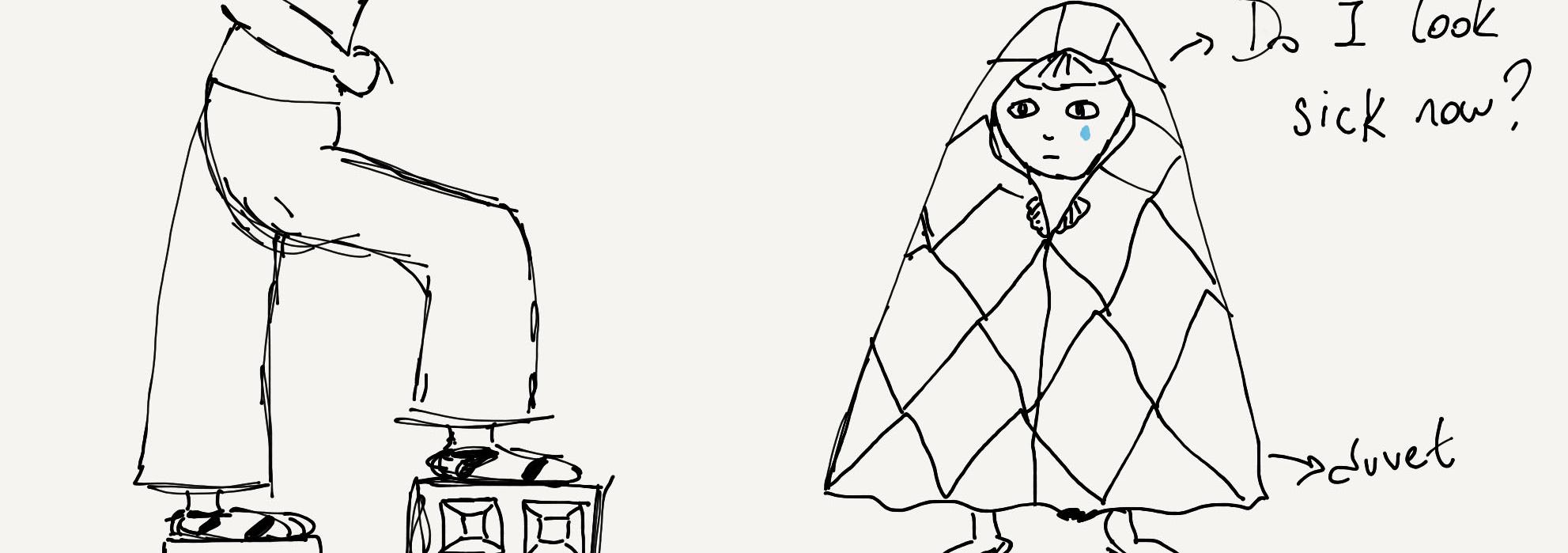

Doing ethnography in a familiar environment required me to be really attentive to what was going on around me. What I find interesting to hear from my informants was the way everyone talks about pain. It has become our routine: “We get tired so easily, I went out for 5 minutes, I feel as if something crashed on me, as if someone attached concrete blocks to my feet and I am trying to walk with them.” This directed my focus to our ‘normality’ because we are so used to FMF, this has become our usual state of being.

Through our conversations, interviews, and gathering life stories, I was able to recognize what was it like before and after the diagnosis of FMF. Prior misdiagnosis and mistreatment had a tremendous effect on my father: “I was diagnosed with rheumatic fever and was prescribed penidure injections for 7 years before the correct diagnosis and it did not help at all. My symptoms were dismissed all those years!” Learning about how my informants reacted to the changes they have experienced shifted my focus on the undocumented, the individual experience of the disease despite the dominant literature of medical studies.

Working collaboratively with my family to gather information was both useful to them as participants and useful to me as the researcher. It had a therapeutic effect on our well-being as opposed to the invisible and invincible nature of our illness.