Doctoral thesis confirms: tastes and smells are often indescribable in language

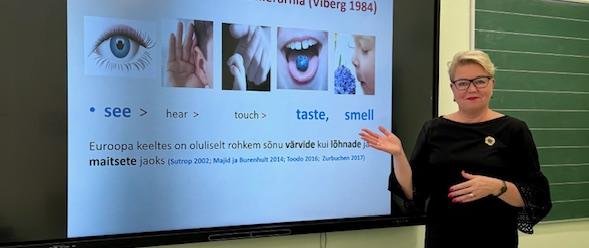

How does freshly baked bread taste? Or what does cleanliness smell like? The world around us is sensory – our senses perceive light, sounds, touch, tastes and smells. What we see and hear is often shared and does not need to be put into words, but when it is not, the experience of touching, tasting and smelling can only be shared through words.

For a long time, global studies on perceptual vocabulary have focused on the visual sense, in particular colour vocabulary. While the vocabulary of colours has a wealth of precise equivalents, when it comes to describing the experience of taste and smell, we tend to get stuck and struggle to find the right words.

Karin Zurbuchen's doctoral thesis at Tallinn University’s School of Humanities explores the words Estonians and Germans use to express three perceptual experiences – colour, taste and smell – and how this reflects the interrelationships between language, culture and perception. German has played a key role in the development of the Estonian written language, yet it has not been used as a reference in similar studies on perceptual vocabulary. This is the gap that the thesis fills.

Karin Zurbuchen's study shows that colours and tastes have their own main vocabulary in both languages, such as punane/rot (red) or hapu/sauer (sour). Smell, on the other hand, is part of the so-called silent language – smells have no vocabulary of their own and are mostly described through evaluative adjectives, such as meeldiv/angenehm (pleasant) or ebameeldiv/unangenehm (unpleasant). It also found that the vocabulary of tastes in languages has changed over time: for example, the word “umami” did not appear at all in earlier studies, but has now been adopted in both languages.

The results also highlight interesting linguistic cultural specificities. For example, the Estonian language distinguishes between the words kibe and mõru, which denote different nuances of bitterness, while in German there is only one word for them – bitter.

On the other hand, the analysis shows that the most commonly used words in both languages are very simple and short and often ambiguous, such as the Estonian magus or the German süß (sweet), which can describe both taste and smell.

In addition, the doctoral thesis confirms that the active olfactory vocabulary contains more negative and less positive words, and that compared to other perceptual vocabulary, taste and smell vocabulary is much more emotional. It is presumably easier to avoid unpleasant tastes than unpleasant smells.

The results of the thesis are important because they help us to understand the active vocabulary of taste and smell in Estonian and German today and how perceptual vocabulary has changed over time, as well as the differences between the vocabulary of taste and smell and that of vision, which is our dominant sense. The active vocabulary of all three perceptual domains studied is similar – on the one hand, it clearly reflects the cultural interconnectedness of the languages, but both languages are also similarly influenced by globalisation and Western European consumer and food culture and practices.

The thesis defence

Karin Zurbuchen is a PhD student at Tallinn University’s School of Humanities. Her doctoral thesis is entitled "An empirical study of Estonian and German active vocabulary of colour, taste and smell".

Public defence of the thesis will take place on 9 October 2025 at 16:00 in Tallinn University Hall M-648.

You can also follow the defence and ask the degree candidate questions through Zoom.

Supervisors are Reili Argus, Professor of Estonian Language at Tallinn University, and Ene Vainik, Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of the Estonian Language.

Opponents are Tuomas Huumo, Professor at the University of Turku, and Ann Veismann, Associate Professor at the University of Tartu.

The thesis is available in the Tallinn University Academic Library environment ETERA.