TLU Plan for Gender Equality and Equal Treatment 2025–2027

To open a TLÜ Gender Equality Plan descriptive document in .pdf format click here.

Introduction

The purpose of Tallinn University (hereinafter TLU) Plan for Gender Equality and Equal Treatment is to increase awareness of gender equality and implement effective measures to ensure equal opportunities and treatment for everyone at the University. The Plan is based on the legislatively state regulated principles of equal treatment and gender equality, Code of Conduct for Research Integrity, as well as EU Commission Guidance and the strategic targets set out in the Welfare Development Plan 2023-2030. Arising from the mission and vision formulated in the University Development Plan, TLU is committed to ensure equal opportunities and a supportive and amicable operative environment for all employees and students regardless of their gender and gender identity, sexual orientation, nationality and ethnic origin, race, religion and belief, disability, age, pregnancy and parenthood or marital status. We are convinced that only through equal treatment, equal opportunities and positive attitude, we will achieve that all groups and individuals can give their best according to their abilities and wishes; therefore, we set an objective of introducing zero tolerance towards any kind of unequal treatment, discrimination and harassment.

The Plan focuses on several key areas where gender inequality or unequal treatment on any other grounds may occur within the context of working as well as teaching and learning. It is essential for TLU to create work and study culture free of discrimination with zero tolerance towards unequal treatment and harassment.

Recruitment and remuneration

It is important to ensure equal opportunities to everyone in the process of selecting and recruiting employees, and on the career paths. Regulations governing employment relationships and remuneration in Tallinn University follow the principle of equal treatment (e.g. clause 2.2. of the TLU Remuneration Regulations sets out that the principle of the equality of employees is adhered to in the process of remuneration) and determine clear criteria applicable to the human lifecycle (e.g. parental leave, conscription service), on the basis of which decisions concerning recruitment and remuneration are made. As far as remuneration of work related to projects is concerned, the principles of the Code of Conduct for Research Integrity agreement are taken as the basis, stating that researchers distribute their resources economically, unselfishly and fairly. Depending on the situation, it may indicate to equal treatment of all participants or special treatment based on justified needs.

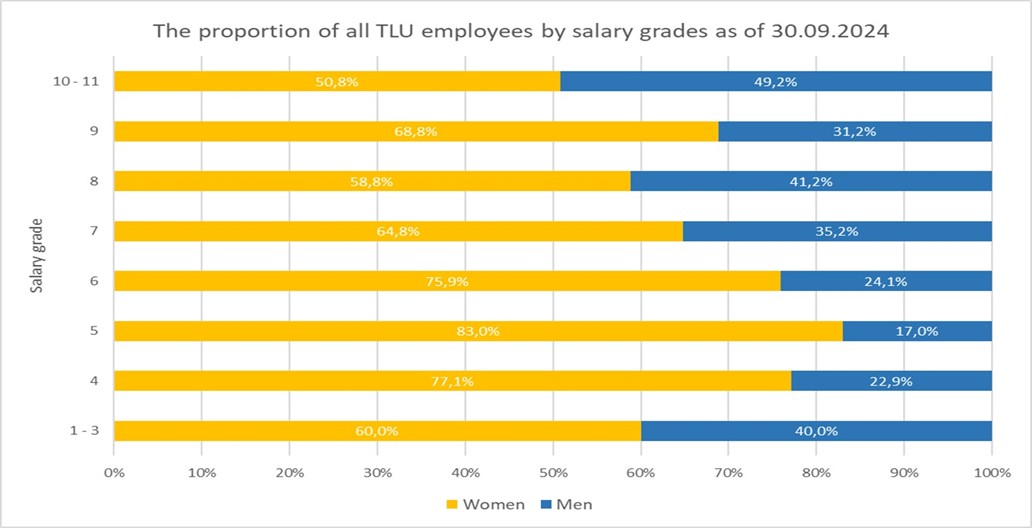

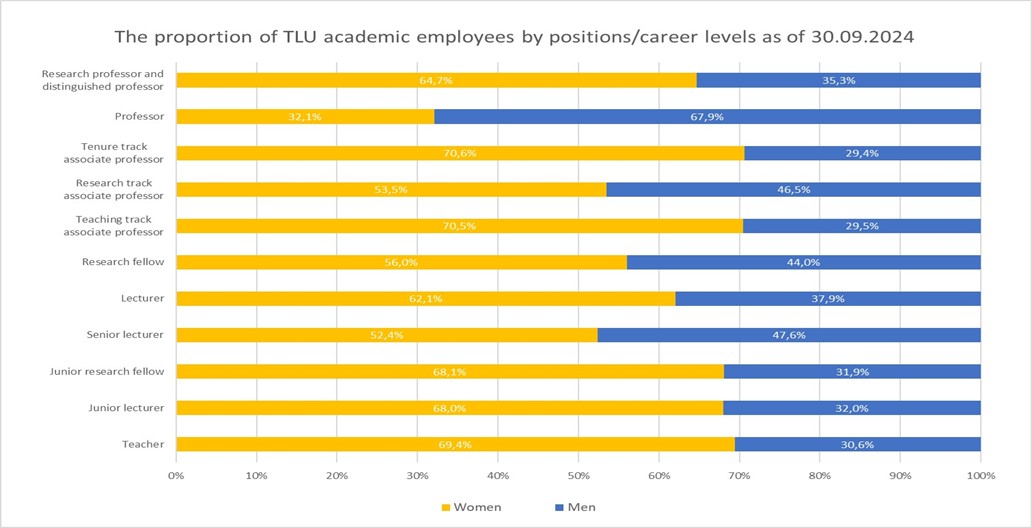

The specificity of Tallinn University lies in the fact that the share of women is significantly higher than the share of men in the collective as a whole as well as among academic employees. Women constituted 69.3% of all employees as of September 2024, and 62.6% of academic employees. The reasons for this trend lie in the discipline-specific main foci and cultural context of universities: humanities, social sciences and education are often deemed to be “soft” domains, more suitable for women. Such attitudes are reflected in the minds of both, men and women. Additionally, the factors may include gender imbalance in Estonian higher education – the ratio of women who attain the level of higher education is significantly higher than that of men – and insufficient funding of higher education that reproduces structural inequality based on the aspect of gender. Teaching is stereotypically considered a feminine field of activity, therefore often less financed in comparison with other fields).

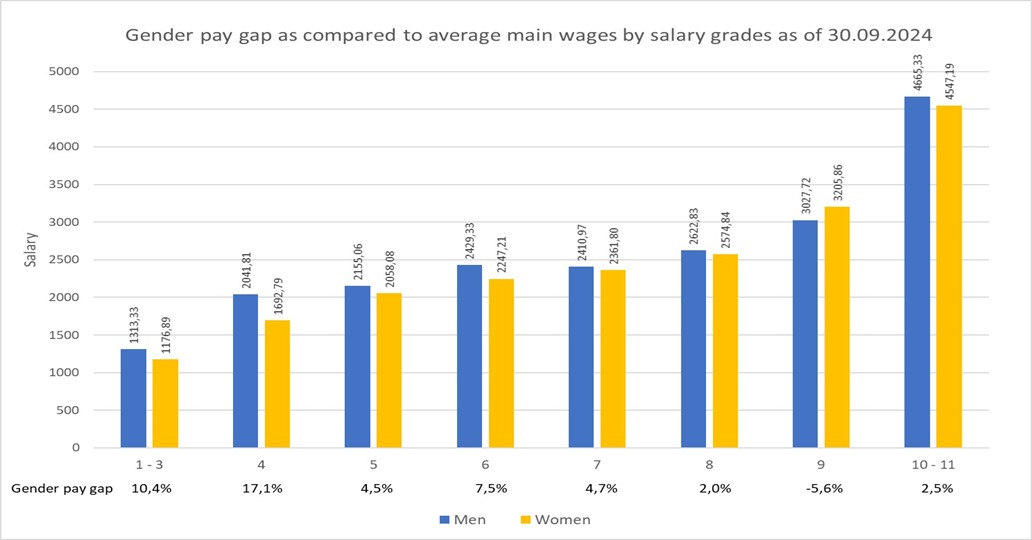

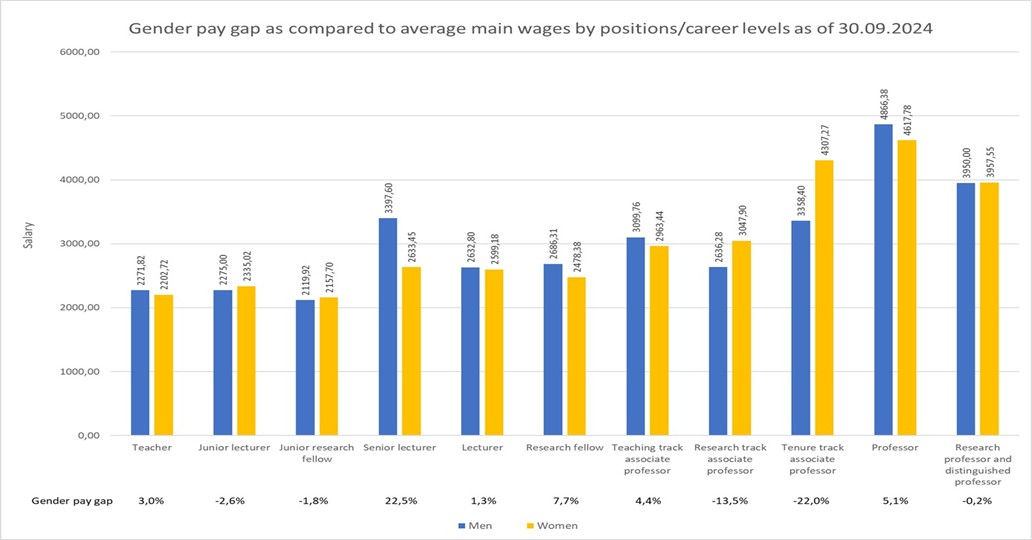

Gender pay gap in Estonia is relatively big (13.1% according to the data of Statistics Estonia of 2023) which is why the University considers it important to monitor gender pay gap. Even though the gender pay gap at the University is considerably lower as compared to the Estonian average but when comparing the actual salary of men and women across all academic positions, the gender pay gap is about 4.6% in favour of men (as of September 2024). The goal is to balance remuneration and career paths to promote equal gender representation in academic and professional development.

TLU has taken steps to collect and analyse data in a manner which enables better understanding of how and why gender distribution as well as age distribution vary in different positions and career levels and by salary components. An overview is available on the University’s webpage University in Numbers in the section Staff and the Action Plan focuses on making salary statistics more transparent within the coming year. Special attention is paid to situations where the gender pay gap at a comparable salary level and considering the average wages of people employed in the same field is higher than 5%.

Action Plan 2025-2027

|

Goal |

Results |

Leader |

Partners |

Deadline |

|

Acknowledging prejudices that occur during recruitment and assessment of work results. Training of all people who are involved in such decision-making processes. |

Colleagues involved in the recruitment process are aware of their potential prejudices and consider their potential impact on decision-making processes. |

Commissioner for Equal Treatment |

Centre for Professional Development |

June 2025, thereafter annually |

|

Statistics about gender pay gap is published |

Statistics about gender pay gap in the entire wages and the main wages is easily available on TLU webpage and it is possible to filter it by academic units and positions and career levels. It is renewed annually. |

Human Resources Manager |

Strategy Office |

December 2025 |

|

The (main) wages are regularly reviewed, having gene pay gap in mind, and if the gap is not justified by varying contribution to work and/or performance, a detailed plan for reducing the gap is created. |

If the gender pay gap is not justified by varying contribution to work and/or performance, the unit has a well-defined plan for reducing the gap. |

Unit directors |

Administrative heads together with the Remuneration Senior Specialist |

Data available for management from November 2025, thereafter annually |

Reconciliation of work and family life

An important area that TLU as an employer pays attention to is the reconciliation of work and family life. Studies indicate that women’s family-related burden of care labour is bigger which reduces their opportunities in scientific career and has an impact on gender equality. In addition, teaching and research frequently means working at unconventional times, such as evenings and weekends, which makes it difficult to reconcile work and family life. TLU rules regulating employment relations consider the time spent on pregnancy and maternity leave, parental leave, conscription service or alternative service. By the abovementioned time periods, the time limits for, e.g. completing a career level, period of assessing previous work results, evaluation period, period of using the sabbatical leave, etc. are extended. As the regulations emphasising equal treatment might not completely ensure that unequal treatment following historically developed attitudes and stereotypes will not occur in practice, it is important to monitor the processes related to the movement on the career path and to intervene, where necessary.

In 2024, the new principles of calculating the work load of academic employees were agreed upon and established which uniformly apply to all academic units and will come into effect in September 2025. After the uniform principles were established the creation of an information system was started for calculating the work load and making it more transparent, thus enabling to monitor how the system of calculating the work load functions. As a result, the agreements made between the superior and the employee concerning the work load will not only be information shared between them but it will be possible to analyse the information from different angles, including the comparison of work load by gender.

Action Plan 2025-2027

|

Goal |

Results |

Leader |

Partners |

Deadline |

|

The information system for calculating the work load is used throughout the University. |

The information about the work load of academic employees is available, comparable and can be analysed. |

Human Resources Manager |

Strategy Office, Academic Affairs Office, Research Administration Office, IT Office, academic units

|

December 2025 |

|

Mapping the need for child day care |

Depending on the mapping results a decision has been taken to offer / not offer child day care (children’s playroom) services on campus |

Human Resources Manager |

Student Union |

December 2025 |

Equal gender representation in management and decision-making processes

Looking at the TLU management structure by gender representation, it appears that the representation of men and women corresponds to the gender structure of the University staff. This means that in the decision-making bodies and positions of managers, the share of women is predominantly higher, whereas in the University Council which deals with economic matters, the representation of men is bigger. First and foremost, it is necessary to create an environment to facilitate the gradual change of attitudes to ensure equal representation of men and women at all levels and therefore one of the goals for the coming years is the gender balance in candidate lists for the elected positions. Though the competence of the candidates is the most important factor in the selection process, the less represented gender should be considered for the positions in case the candidates are equally strong but have different gender.

Action Plan 2025-2027

|

Goal |

Results |

Leader |

Partners |

Deadline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The candidate lists for the elected positions in the University are gender balanced or correspond to the gender distribution of employees |

Supports gender-balanced representation in managerial bodies |

Commissioner for Equal Treatment |

Personnel Office, Rectorate and academic units |

December 2027 |

|

Training of leaders / development of leadership competences where attention is also paid to equal treatment |

More fair and inclusive organisational culture |

Centre for Professional Development |

Commissioner for Equal Treatment |

December 2027 |

Organisational culture and conflicts

TLU has taken important steps to improve the organisational culture, for example, joining the Estonian Code of Conduct for Research Integrity agreement and the implementation of good academic practice in TLU. At the same time, it is important to continue with preventive measures to ensure equal treatment and gender equality with the focus on awareness-raising activities and trainings. The University has created a transparent and fair system that enables to process cases of discrimination and harassment as well as those of bullying. It is also essential for Tallinn University to create and maintain an amicable environment for studying, teaching, research and work for all University members. In order to achieve this, we rely on the principles of restorative justice with the purpose of creating and maintaining friendly and collaborative working and studying environment. The goal of restorative justice is to restore the balance between the community and individuals by offering possibilities for assuming responsibility, repairing damages and restoring relationships and trust. Restorative approach thus relies on the idea that the organisation is stronger and more sustainable when its members collaborate and support one another.

Action Plan 2025-2027

|

Goal |

Results |

Leader |

Partners |

Deadline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Each academic unit and support unit have 1-2 persons who possess skills and will to mediate conflicts by applying principles of restorative justice |

Practices based on restorative justice form part of the University culture pattern when resolving tensions and conflicts |

Commissioner for Equal Treatment |

Community of voluntary conflict mediators |

December 2026 |

|

Intervention / speak up culture – create awareness of the importance of supporting colleagues and fellow learners and of the impact of intervention in possible situations of bullying and discrimination

|

The University studying and working environment offers more mutual support and is more collaborative |

Commissioner for Equal Treatment |

In cooperation with five public universities |

June 2025 |

|

Raising the awareness of students on the matters of sexual and gender-based violence, incl. harassment |

Students are aware of the dangers arising from gender inequality (incl. gender-based violence) and possibilities of providing help. |

Academic Affairs Office |

Marketing and Communications Office, Student Union, Social Insurance Board |

Annually in October |

Integrating the gender perspective into research and studies

TLU has researchers and research groups conducting high-level research in the field of gender studies and more generally on the topics of equal treatment. A NGO The Estonian Women’s Studies and Resource Centre has operated in the rooms of TLU for more than 20 years, and all students and academic staff of the University can use its library. Increasing the visibility of the works of women researchers and scientists and raising broader awareness on the topic of gender equality help foster equality in the academic learning and research environment. Improving the study programmes and study materials, having the gender issues in mind, is also an important step in promoting equality.

Action Plan 2025-2027

|

Goal |

Results |

Leader |

Partners |

Deadline |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

We offer a training programme to academic staff to increase awareness on the topic of gender equality |

Increased awareness on the topics of gender equality and equal treatment and teaching practices are compatible with the principles of equal treatment. |

Commissioner for Equal Treatment |

Centre for Learning and Teaching |

December 2026 |

SUMMARY

TLU Plan for Gender Equality and Equal Treatment provides a comprehensive network with the aim of creating a work and study environment and University culture which supports the equality and integrity of all its members regardless of their gender, nationality, age, beliefs or any other traits. The Plan focuses on key areas where unequal treatment may occur and aims to set out concrete goals in each area and appoint leaders and deadlines. The Plan has been compiled in the knowledge that the promotion of equal treatment is an ongoing process and by taking small steps greater results can be achieved, thereby acknowledging that the successful implementation of the Plan lies with all University members.

An overview of the implementation of the Plan for Gender Equality and Equal Treatment is to be provided annually to the Senate and the most important activities and results related to gender equality are presented in the Annual Report.