Water, Memory, and Vulnerable Bodies

Professor of English Julia Kuznetski has recently published a scholarly article in the journal Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction , titled “Scalar Anglosphere: Wasteocene Waters and Vulnerable Bodies in Chioma Okereke’s Water Baby,” in which she analyzes the novel by young British-Nigerian writerChioma Okereke from the perspectives of blue humanities and decolonial critique. The choice is not accidental. Kuznetski’s research areas include literature and culture of the English-speaking world, the work of women writers, and the social, political, and environmental dimensions of literature—all of which are addressed in Okereke’s novel. Water Baby (2024) was also included in last year’s longlist of British Climate Fiction Prize.

Nigeria is one of the largest English-speaking countries in the world, surpassed in population only by the United States. The birth country of English ,, Great Britain, no longer holds the leadership in the number of its speakers. . Anglophone literature from postcolonial countries is particularly vibrant and stimulating: it raises questions that concern not only local communities but the entire world. At the same time, these regions are often among the most vulnerable both politically and ecologically, and it is there that the consequences of the environmental crisis are felt most acutely.

Kuznetski has long worked on postcolonial literature and ecocriticism, one important branch of which is the proliferating field of blue humanities. This line of research focuses on the role and representation of water in culture—literature, art, and film—in all its forms, whether seas, rivers, groundwater, ice, clouds, or the world ocean. lue humanities are premised on the idea that humans are themselves bodies of water: we are largely composed of water and are in constant, often invisible interconnection with our watery environment. This entanglement makes us simultaneously alive and vulnerable, because water carries not only life but also pollution, memory, and risk.

“Water Baby” – life on the Lagos Lagoon

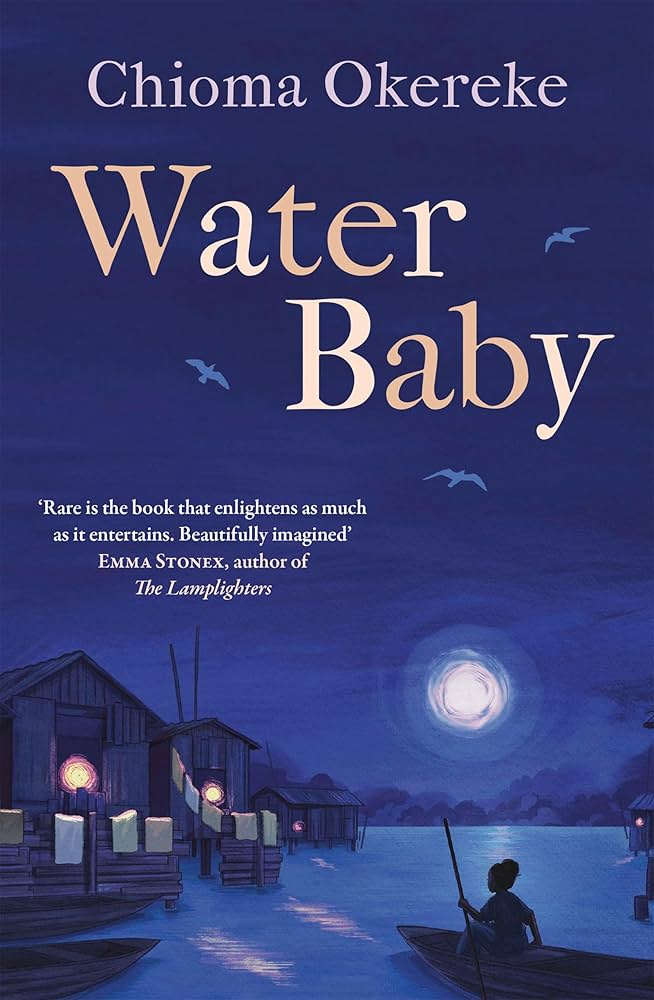

Water Baby depicts the colourful, noisy, and viscerally odorous life of the floating slum of Makoko on the Lagos Lagoon, set against the cold, clean, comfortable, and indifferent European space that the protagonist briefly encounters. The narrator and protagonist of the novel is a 19-year-old water-taxi driver nicknamed Baby, whose everyday life unfolds on and in the water, inseparable from her community and its customs, beliefs, and expectations. Makoko is a place where houses stand on stilts, canals serve as streets, and life depends directly on the lagoon: it is the community’s source of work and food, but also a marker of identity. Water in the book is simultaneously a source of life and a collector of toxic pollution. It carries memory, connects the living with their ancestors, and is both a creative force and a bringer of death. This ambivalence is a central feature of the novel: the text intertwines a realist portrayal of poverty, environmental pollution, and postcolonial urban politics with African cosmology and the spirit world. Alongside the living, the spirits of ancestors and the recently deceased are present, and the boundary between life and death, humans and nature, is blurred.

Global problems in concentrate

Kuznetski notes in her article that while Water Baby tells the story of a single community, it simultaneously reveals broader issuesand power structures of the postcolonial world. Makoko is not a random slum, but a point of intersection between colonial history, urbanisation, and global capitalism. Nigeria itself came into existence as a result of administrative decisions made by theBritish colonial rule, and many of today’s environmental and social problems are long-term consequences of those decisions.

The Lagos Lagoon embodies many of these contradictions. On the one hand, luxurious developments rise along its shores; on the other, wetlands are destroyed, sand forming the coastline is mined, and industrial and household waste accumulates. Kuznetski emphasizes that the novel helps us see how such processes directly affect both the regional ecosystem and human bodies, health, and everyday survival. Since a single lagoon is part of a larger aquatic environment and, on a broader scale, the world ocean, it becomes a place where local lives and global powers intersect—and where a “local” environmental crisis turns out to be planetary.

Here the concept of the Wasteocene—or the “age of waste”—is useful, as it helps us understand that although we all live in an era of environmental crisis, we do not experience it equally. This is precisely why the widely used term “Anthropocene” is no longer sufficient, as the “age of humans” refers to an abstract “human” who is said to have caused the problems of the contemporary world, downy to geological alterations. . At the same time, there are places and communities in the world that have contributed far less to the creation of these problems, yet bear their consequences most acutely. Pollution, and political neglect accumulate in these places to such an extent that the people living there and their stories themselves become a kind of “waste.” Makoko as depicted in the book is one such living space—made vulnerable and unstable for the sake of “development” of others. An important way out of this “waste status” is the telling of different kinds of stories, in which the lives of vulnerable and invisible communities are foregrounded, made visible, and even tangible—through voices, sensations, and smells that are vividly present in this book. In this way, Okereke’s novel reverses the gaze, portraying the water village not as a dirty, backward blank spot on the map, but as a real, living place. At the same time, the author shows that “reality” depends on the perspective, and that there is a deep divide between global climate conferences and local lived experience.

Traumatic memories and the spirit world

Being the sourceof life and the central element of the novel, water also carries memory, connects generations, and preserves stories that official history tends to erase. This, in turn, enables the novel to depict so-called slow violence—harm that does not manifest in a single dramatic moment, but accumulates gradually: toxic water, depleting fish, diseases, and loss. One of the most tragic threads in the novel is the accident that strikes Baby’s family, in which a child dies as a result of political decisions and environmental conditions. At this moment, fast and slow violence converge, and water becomes the repository of a deep family trauma. Toward the end of the novel, an African cosmological worldview becomes central, one in which humans are not separated from nature, but are part of a chain of life forms. Baby’s real name, Yemoja, refers to the Yoruba water goddess, the mother of all fish, and emphasises the connection between water, origin, and communal life. The fluidity and ambivalence inherent to water dissolve boundaries between light and darkness, life and death, and reality, memory, and magic become embedded.

The full text of the scholarly article has been published in the journal Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction (2026). If you wish to read the complete article, you can find it HERE

The article was completed with the support of the Estonian Research Council: grant PRG2592, “Memory and Environment: The Environmental Impact of Violent Histories in Transnational European Literature”

Julia Kuznetski has previously written about the blue humanities in Müürileht.